Hey, it happens to us all. I’m healthy as a horse, but a body part was bugging me, so at my annual check up I asked to see a specialist. I love my family doc, er I mean “primary care,” and I love this specialist. They’re the best there is. And they’re victims of the system as much as we. I’m grateful they’re here just when I need them, with all their years of training and miraculous skills. I don’t want to cause them trouble, so let’s call it “body part X.”

Hey, it happens to us all. I’m healthy as a horse, but a body part was bugging me, so at my annual check up I asked to see a specialist. I love my family doc, er I mean “primary care,” and I love this specialist. They’re the best there is. And they’re victims of the system as much as we. I’m grateful they’re here just when I need them, with all their years of training and miraculous skills. I don’t want to cause them trouble, so let’s call it “body part X.”

It took months to get authorization for the specialist, thanks to insurance lunacy. Meanwhile X got worse, but still I expected just a routine new prescription.

The new doc walked in, took one look, and said, “You’ve got [deleted] here, and also there. You can go on like that for a while, and I could just write you another prescription for Y [as it’s been handled before]. But you’ll be back in a year because it will get worse. It’s not for me to tell you what to do, but we can replace [body part X] with an implant…

“Outpatient surgery takes 20 minutes, insurance pays for it all because it’s legally classified as ‘medically necessary’ since otherwise you’re going to lose your Z [essential function]. Then you can forget about the problem, you’ll be done.” (And no, it wasn’t prostate cancer.)

“Outpatient surgery”? So professional. Me? I’ve just been told, “you’re getting a knife in a real scary place.”

The specialist (I do like him) told me later that at that first meeting, he then proceeded to outline my options for the different available types of inplants, and following surgery, what functional abilities each implant type would give me. I was with him less than 20 minutes. Next he sent me on to his medical assistant to be checked by one more machine, who sent me to their lady “surgery coordinator.” By which time I was hit by a barrage of panic from my belly.

I’ve never had more than a tooth pulled in my life, and OK, I’ve always been a “fraidy cat.” And all I could think of was “Surgery. Surgery? Surgery — there?”

From the first mention of “surgery,” clearly I was in trauma. But why did this occur to no one, with so many professionals there? They seemed so oblivious that anything upsetting could possibly have occured, I was afraid to show it.

“We’ve discovered in our work in trauma that going to the gynecologist, pediatrician, social worker at school, any of the helping professions, can be traumatic,” says trauma expert Dr. Mary Jo Barrett (below right). “People with prior trauma, especially, experience their attempts to get help from the medical system as traumatic – because they experience it as a threat to their bodies.” [FN1]

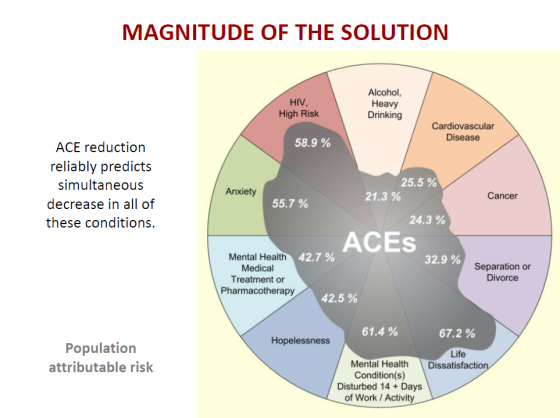

And according to the ACE Study, roughly 50% of us suffer one or more types of Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) trauma. That means half of us are going to experience such a medical issue as trauma. Including clearly me.

And according to the ACE Study, roughly 50% of us suffer one or more types of Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) trauma. That means half of us are going to experience such a medical issue as trauma. Including clearly me.

But in fact any human who’s a mammal will experience something like this as trauma, science is just starting to show. And even the most well-meaning, kindly medical personnel have never gotten the memo on what is trauma and how their system contributes to it.

Not to mention the legions of pretty much heartless medical personnel who have had their humanity forcibly ripped out of them by their training. Psychiatric expert Dr. Daniel Siegel, MD, says he almost quit med school when he realized he was being deliberately trained to destroy his emotions and view patients as machinery to be fixed, in the name of better performance.

No Time to Think – Let Alone Feel

Not to mention the insurance companies who now force doctors to stay glued to a stop-watch while seeing patients. Docs are forced to spend no more than X (pardon the pun) minutes per patient, no matter what, or they won’t be paid, can’t pay their staff or their astronomical malpractise insurance premiums, and must close their doors.

Upset? Shove it. Suddenly there I was with the “surgery coordinator,” and I had no time to panic, feel any emotion, or even to think. Wham, she hit me with a barrage of wildly complex surgery insurance questions involving a five-way tangle between my HMO, the specialist, the primary doc, the doctors’ “medical group,” and the hospital– made more complex by the fact that my insurance was about to change radically in three months. Worse, she was the type who quickly rattles off a list of in-house acronyms that only an insurance exec could understand, then says “OK?”

No, it was most definitely not ok. In fact with all my experience handling insurance companies over many years, 15 years experience interviewing engineers about rocket science, a BS in Math and 3 foreign languages — I still couldn’t understand a word she said. Surely she’s good at what she does, but her ability to explain what she does to another human being was sub zero.

As I began to drown under her spiel, that internal voice just got louder: “Surgery. Surgery? Surgery — there?”

On she went with questions about my meds, vitamins, lifestyle, and complicated instructions about new meds they were going to give me before surgery, and when to take what in a detailed month-long schedule. The level of detail would have overwhelmed anyone who’d just been given good news. By the time she was done rattling, the office was about to close at 5 pm and I was ushered out.

No more than two minutes of the entire two hour ordeal had been allowed for discussion of, or even for me to think about, the real Square One decision at hand: Surgery? Go for surgery, or not?

“Surgery. Surgery? Surgery — there?” It seemed like a nightmare from which I’d soon wake up. As it turned out, that feeling lasted about ten days. I kept thinking, “Oh, this is just a bad dream. I’ll wake up any minute.” No such luck. Somehow I made it through an evening of appointments straight until 9 pm, drove home and collapsed at 11 pm.

Involuntary Reaction to Survival Threat

“Medical procedures send many of the cues to the nervous system that physical abuse has,” warns Dr. Stephen Porges (left). “We need to be very careful about how we deal with people and whether or not even medical practices trigger some of the features of PTSD…

“Medical procedures send many of the cues to the nervous system that physical abuse has,” warns Dr. Stephen Porges (left). “We need to be very careful about how we deal with people and whether or not even medical practices trigger some of the features of PTSD…

“Our clothing is taken away. They remove your glasses. We’re left in a public place and all predictability is gone. Many of the features that our nervous system uses to regulate and feel safe are disrupted,” says Porges. [FN2]

“And one of the most potent triggers of neuroception un-safety, is low-frequency sounds which the neurological system interprets as ‘predator.’ In ‘Peter and the Wolf,’ friendly characters are always the violins, flute, and oboe. Predator is always conveyed via lower frequency sounds. Medical environments are dominated by low frequency sounds of ventilation systems and equipment. Our nervous system responds, without our awareness, to these acoustic features and shifts physiological state.”

Medical pronouncements about what’s going to happen to our bodies, and medical environments generally “trigger ‘neuroception’,” Porges explains, “the neural circuits regulating the autonomic nervous system” tell our bodies that we are under threat. The news goes straight to our brain stem which takes action, without ever involving our thinking brain. Something entirely involuntary happens.

“Neuroception is not perception. It does not require an awareness of what’s going on,” says Porges. “Throw away the word ‘perception.’ Neuroception is detection without awareness. It is a neural circuit that evaluates risk in the environment from a variety of cues. When our mammalian social engagement system is working and down-regulating defenses, we feel calm, we hug people, we look at them and we feel good. But in response to danger, our sympathetic nervous system takes control and supports metabolic motor activity for fight/flight. But next, if that doesn’t get us to safety, the ancient unmyelinated vagal circuit shuts us down,” says Porges, literally describing shock.

He gives an example: himself. “I had to get an MRI. Many of my colleagues conduct research using the MRI, and I thought, ‘This will be a very interesting experience.’ You have to lay down flat on a platform and the platform is moved into the magnet. I enthusiastically lay down on the platform for this new experience. I felt really good. I was not anxious…

“Slowly the platform moved into a very small opening of the MRI magnet. When it got up to my forehead, I said, “Could I get a glass of water?” They pushed me out and I took my glass of water. I lay down again and it moved until my nose was in the magnetic. I said, ‘I can’t do this.’ I could not deal with the confined space; it basically was putting me into a panic attack… And an MRI produces massive amounts of low-frequency sounds…

“My perceptions, my cognitions, were not compatible with my body’s response. I wanted to have the MRI. It wasn’t dangerous. But, something happened to my body when I entered the MRI. There were certain cues that my nervous system was detecting and those cues triggered a defensive of wanting to mobilize to get out of there. And I couldn’t do anything about it. I couldn’t think my way out of it. I couldn’t even close my eyes and visualize my way out of it. I had to get out of there! Now when I have a MRI, I take medication.”

I could go on. I could tell you how I dealt with the question “should I have this surgery” the very next day, by getting a second opinion in my area, and was told “Yes, and soon.”

I could tell you how after a few days, I realized that the next looming question was what type of implant to choose, how long it would take each type of implant to get approved through the insurance maze, and where each type would leave my body functions after surgery. So I put out queries to the second specialist, and to three personal friends in Maryland, New York, and Illinois who are doctors, who all polled their colleague specialists in body part X. All of them came back with conflicting advice.

I didn’t ask my first specialist because I’d been told by the surgery coordinator to wait for a packet by mail, believing it would tell me how to select implants. But when it came a week later, it didn’t mention implants.

As noted, the specialist said later that at our first meeting, he did outline my options for the different types of implants. I was with him less than 20 minutes, half of which was a physical exam with a lot of machines.

Perhaps he gave a good briefing, but I was in “Surgery!?!” trauma, and my brain was out to lunch — like Dr. Porges in the MRI. If so, didn’t he realize I might be too preoccupied by the word “Surgery” to hear all those critical complex details immediately?

Perhaps he just read me an incomprehensible list in under a minute. I’ll never know; I simply can not remember even a single mention that first day of this issue, which is still tying up many of my waking hours at this writing.

Because now, nine days later, I have his read-out, and read-outs from the other four specialists – and none of them agree on the implants. Some of them even imply that the type my specialist is recommending could be a health hazard long term. And none of them have the remotest idea there might be a bit of trauma after all this at my end.

It’s 1 am and time to post this blog — so I can get up tomorrow and try to get this straightened out in time to select the correct implants, in time to get them authorized by insurance, in time for — surgery.

——————

Kathy’s news blogs expand on her book “DON’T TRY THIS AT HOME: The Silent Epidemic of Attachment Disorder—How I accidentally regressed myself back to infancy and healed it all.” Watch for the continuing series each Friday, as she explores her journey of recovery by learning the hard way about Attachment Disorder in adults, adult Attachment Theory, and the Adult Attachment Interview.

Footnotes

FN1 Barrett, Mary Jo, MSW, “Addressing PTSD: How to Treat the Patient without Further Trauma,”

NICABM Webinar, June 29, 2011. Dr. Barrett’s latest book is “Treating Complex Trauma: A Relational Blueprint for Collaboration and Change,” orders are here: http://goo.gl/SEiWVD and http://www.centerforcontextualchange.org/publishedworks.html

FN2 Porges, Stephen, PhD, “The Polyvagal Theory for Treating Trauma,” 2011, http://stephenporges.com/images/stephen%20porges%20interview%20nicabm.pdf

—“Body, Brain, Behavior: How Polyvagal Theory Expands Our Healing Paradigm,” 2013, http://stephenporges.com/images/NICABM%202013.pdf

—“Beyond the Brain: Vagal System Holds the Secret to Treating Trauma,” 2013, http://stephenporges.com/images/nicabm2.pdf

—”Polyvagal theory: phylogenetic substrates of a social nervous system,” International Journal of Psycho-physiology 42, 2001, Dept. of Psychiatry, Univ. Illinois Chicago, www.wisebrain.org/Polyvagal_Theory.pdf

![]()