“To prevent childhood trauma, pediatricians screen children and their parents…and sometimes, just parents…for childhood trauma”

— guest blog by Jane Ellen Stevens, Editor, ACEsTooHigh.com and ACEsConnection.com

When parents bring their four-month-olds to a well-baby checkup at the Children’s Clinic in Portland, OR, Drs. Teri Petersen, R.J. Gillespie and their 15 other partners ask the parents about their adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). [Tabitha Lawson of Portland, OR with her two children, who greatly benefited from the new program; more below]

When parents bring their four-month-olds to a well-baby checkup at the Children’s Clinic in Portland, OR, Drs. Teri Petersen, R.J. Gillespie and their 15 other partners ask the parents about their adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). [Tabitha Lawson of Portland, OR with her two children, who greatly benefited from the new program; more below]

When parents bring a child who’s bouncing off the walls and having nightmares to the Bayview Child Health Center in San Francisco, Dr. Nadine Burke Harris doesn’t ask: “What’s wrong with this child?” Instead, she asks, “What happened to this child?” and calculates the child’s ACE score.

In rural northern Michigan, a teacher tells a parent that her “problem” child has ADHD and needs drugs. The parent brings the child to see Dr. Tina Marie Hahn, who experienced more childhood trauma than most people. Instead of writing a prescription, Hahn has a heart-to-heart conversation with the parent and the child about what’s happening in their lives that might be leading to the behavior, and figures out the child’s ACE score.

What’s an ACE score? Think of it as a cholesterol score for childhood trauma.

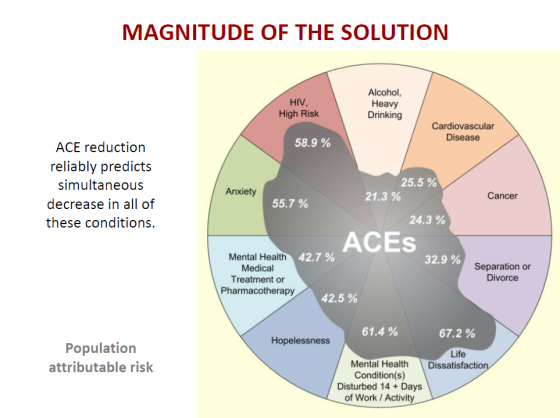

Why is it important? Because childhood trauma can cause the adult onset of chronic disease (including cancer, heart disease and diabetes), mental illness, violence, becoming a victim of violence, divorce, broken bones, obesity, teen and unwanted pregnancies, and work absences.

The CDC’s Adverse Childhood Experiences Study (ACE Study) measured 10 types of childhood adversity: sexual, physical and verbal abuse, and physical and emotional neglect; and five types of family dysfunction – witnessing a mother being abused, a household member who’s an alcoholic or drug user, who’s been imprisoned, or diagnosed with mental illness, or loss of a parent through separation or divorce. (There are, of course, other types of trauma, but those were not measured in this study. Other ACE surveys are beginning to include other types of trauma.)

Each type of trauma — not the number of incidents of each trauma — was given an ACE score of 1. So, a person who has been emotionally abused, physically neglected and grew up with an alcoholic father who beat up his wife would have an ACE score of 4.

The ACE Study found that childhood trauma was very common — two-thirds of the 17,000 mostly white, middle-class, college-educated participants (all had jobs and great health care because they were members of Kaiser Permanene) experienced at least one type of severe childhood trauma. Most had suffered two or more.

The more types of childhood trauma a person has, the higher the risk of medical, mental and social problems as an adult (Got Your ACE Score?). Compared with people who have zero ACEs, people with an ACEs score of 4 are twice as likely to be smokers, 12 times more likely to attempt suicide, seven times more likely to be alcoholic, and 10 times more likely to inject street drugs. Compared to people with zero ACEs, people with an ACE score of 6 have a shorter lifespan – by 20 years.

Twenty-two states and Washington, D.C., have done their own ACE surveys, with similar results.

The ACE Study is part of a perfect storm of research emerging over the last 20 years that is revolutionizing our understanding of human development. Brain research shows how the toxic stress of trauma damages the structure and function of children’s brains, which can explain their hyperactivity, inattentiveness, angry outbursts and other behavior. This affects their ability to learn in school, and leads them to use drugs, alcohol, thrill sports, food and/or work as coping mechanisms.

Biomedical researchers discovered that toxic stress experienced as a child can linger in the body to cause chronic inflammation as an adult, resulting in heart and auto-immune diseases, such as arthritis. And epigenetic research shows that the social and emotional environment can turn genes on and off, and childhood trauma can be passed from parent to child to grandchild.

Let’s put this another way: A huge chunk of the billions upon billions of dollars that Americans spend on health care, emergency services, social services and criminal justice boils down to what happens – or doesn’t happen — to children in their families and communities.

The pediatricians mentioned in this article know that, and they also know that if they intervene early enough to stop or prevent childhood trauma by building resilience factors in children and families, children won’t suffer, and they’ll have happier, healthier lives as adults.

Pediatricians aren’t just about sore throats and ear infections anymore, says Gillespie. “This is a culture shift. We’re here to support families.”

The profession is moving away from looking solely at healing a child, to healing a family and a community. For the last several years, the American Academy of Pediatrics has been helping pediatricians create medical homes where all needs of children and their families are met, including “specialty care, educational services, out-of-home care, family support, and other public and private community services that are important for the overall health of the child and family.”

Two years ago, the AAP encouraged pediatricians to also address adverse childhood experiences and toxic stress in early childhood. Last month, AAP President Dr. James Perrin launched a new initiative, the Center on Healthy Resilient Children, to “coordinate the academy’s response to the issue of adverse childhood experiences, the promotion of healthy development, and the prevention of toxic stress.”

Feeling overwhelmed…and someone to turn to

When Tabitha Lawson brought her four-month-old son in to the Children’s Clinic in Portland, OR, they both were having a hard time. Unlike her 6-year-old daughter, he wasn’t an easy baby. He had colic, and Tabitha and her husband were under stress from his long bouts of crying.

“I was feeling overwhelmed,” she recalls. “I had no breaks. I work full time. From my job to my house is five minutes, where I’d go into my other life mode, and every evening, the scream-outs.”

She filled out a survey with 10 questions about her adverse childhood experiences (ACEs)… click here to READ MORE…

![]()

Great post! I wish to subscribe to your newsletter.