Dr. Daniel J. Siegel, MD (far left) introduced me to brain science, and I write about brain scientists like him ‘cos they saved my life. Without them, I’d still be a successful, all-head talk technical writer for Pentagon sales. I’d be unaware of my childhood attachment trauma, unable to feel my past, dissociated, and miserable with anxiety. My cholesterol would still be over 240, my kidneys headed for failure.

Dr. Daniel J. Siegel, MD (far left) introduced me to brain science, and I write about brain scientists like him ‘cos they saved my life. Without them, I’d still be a successful, all-head talk technical writer for Pentagon sales. I’d be unaware of my childhood attachment trauma, unable to feel my past, dissociated, and miserable with anxiety. My cholesterol would still be over 240, my kidneys headed for failure.

But in March 2011, I clicked on the wrong link in a friend’s email and ended up watching a Dan Siegel webinar on how the brain works in trauma. [FN1] That’s where my healing began. Siegel flies around the world trying to alert parents and others about how childhood experiences affect the brain. “You sent us a brain in the mail !” Anderson Cooper exclaims in this Sept. 2012 Anderson Live clip. [FN2]

Dan Siegel is sooo relevant to the May 22 New York Times’ dig against Dr. Bessel van der Kolk for speaking of “repressed memories.” If it’s traumatic, we remember it, period, the Times says; “Harvard psychologist Richard McNally called the idea of repressed memories ‘the worst catastrophe to befall the mental health field since the lobotomy’.” But many of McNally’s peers said his allegation wasn’t proven. Harvard’s Lisa Najavits called McNally’s statement “disappointing… landing too forcefully on one side…by no means an end to the debate.” [ FN3]

Siegel’s work suggests that the Times best go back to science school. Dr. Siegel shows extensively that if it’s traumatic, we may very well not remember it coherently.

More important, we almost certainly won’t be able to feel the bodily feelings caused by the trauma, which are still stuck in our bodies. And until we can feel those, we won’t be able to heal the trauma. Siegel illuminates the numerous brain mechanisms which can cause our entire memory system to be fragmented and to misfire badly.

In that first webinar I saw by accident, Siegel said he got started in psychiatry in the 1980s studying the hippocampus, which integrates raw incoming sensory data, into composite conscious memory. Siegel shows there are (at least) four ways in which humans may not remember traumatic events – because their hippocampus wasn’t working.

Implicit Memory

Check out the history of the word “re-member”– in Shakespeare, for example. “Re-member” literally means putting parts of our body (members) back together again, ie, “getting ourselves together.” And now science has shown: memories actually start in the body, not in the thinking brain.

Check out the history of the word “re-member”– in Shakespeare, for example. “Re-member” literally means putting parts of our body (members) back together again, ie, “getting ourselves together.” And now science has shown: memories actually start in the body, not in the thinking brain.

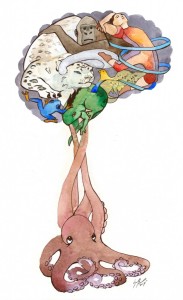

Memories start as raw incoming sensory data. And if the hippocampus isn’t on duty, the body is as far as memories get; memories get stuck in the body. (Illustration shows the “hippo” as a curved grey area center of brain by dancer’s foot. Credit: “The Brain Forest,” Copyright © 2012 by Dr. Stéphane Treyvaud. All rights reserved, at http://www.mindful.ca/in-detail/the-sixtine-brain/ ).

Say you’ve never seen a video, TV, or film; go back before that — to most of human history. Siegel explains that if a dog approaches me, for example, my brain can’t just “take a video”and give me a whole, coherent overview, with headline “this is a dog.” It also doesn’t automatically give me a date of today for this dog here, now. Nor does it automatically tell me that I saw another dog back in 1994 and that was a different dog.

Instead, says Siegel, first, I get a flood of distinct sensory inputs which have nothing to do with each other – or with thought. I get discrete packets of sensory data from the eyes, ears, nose, and other parts of my body. My sense of sight gets a visual “look” of the dog; my sense of smell gets a whiff; my ears may hear a bark or pant. All three are entirely separate incoming sensory data. If a bottle of milk were coming, I’d get a touch memory as to its temperature from finger nerves, a taste memory from lingual nerves, etc.

These bits of incoming data are “implicit memory,” Siegel explains, “changes in synaptic connections…like puzzle pieces.” Each one is a separate sensory memory housed primarily in the nerves reporting in from the body parts where it happened — optical nerve, olfactory nerve, auditory nerve and so on.

Each of those nerves also reports the different implicit data to the non-thinking instinctive brain stem, which also stores parts of these memories and — this is key — without being able to integrate them. The lizard and frog in the cartoon represent the brain stem, ‘cos it functions at about the level they do – reflexively and by instinct. No integration, no thinking.

But: what if the dog (or any other being or event) is hostile? Now, I get an additional flood of unrelated data: my gut gets tight, my heart rate goes up, breath quickens, leg muscles tense to run. It all happens by instinct, instantly, and it bypasses thought altogether. Again: no thinking involved.

Check out the octopus at bottom of the cartoon. “Around our heart, lungs and intestines, we have a web of nerve cells so complex as to correspond in size to the brain of a cat,” says illustration author Dr. Stéphane Treyvaud. “Similar webs of nerve cells may also be found around the muscles.” It’s represented by the head and near arms of the octopus at bottom — and as Treyvaud notes elsewhere, he learned this in his studies with Dan Siegel. [FN4]

Reporting up from all those visceral nerves of the body cavity is the vagus (10th cranial) nerve, which dumps all this lower body sensory data into the primitive brain stem, shown as the longer arms of the octopus reaching up to the green brain stem lizard. Siegel and his colleague Dr. Stephen Porges write extensively on the neuroscience of this. [FN5]

Siegel refers to everything under the thinking frontal cortex as the “downstairs brain,” and this octopus is a good visual. Because if the dog, or anything else, is hostile, not only do I have all those sight, smell, and sound data packets to manage -– I’m also hit with a flood of “downstairs” bodily data packets.

Now what? Well, now I need my hippocampus to be working, or I’m in serious trouble. Let that sink in until next week.

——————————

Kathy’s news blogs expand on her book “DON’T TRY THIS AT HOME: The Silent Epidemic of Attachment Disorder—How I accidentally regressed myself back to infancy and healed it all.” Watch for the continuing series each Friday, as she explores her journey of recovery by learning the hard way about Attachment Disorder in adults, adult Attachment Theory, and the Adult Attachment Interview.

Footnotes

Daniel J. Siegel, MD, is clinical professor of psychiatry at the UCLA School of Medicine on the faculty of the Center for Culture, Brain, and Development and founding co-director of the Mindful Awareness Research Center. He is a Distinguished Fellow of the American Psychiatric Association and Executive Director of the Mindsight Institute. He is also Founding Editor for the Norton Professional Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology which contains over three dozen textbooks.

FN1 Siegel, Daniel J., MD, “How Mindfulness Can Change the Wiring of Our Brains,” October 12, 2011 webcast, National Institute for the Clinical Application of Behavioral Medicine (NICABM), www.nicabm.com http://www.nicabm.com/mindfulness-2011-new/

FN2 Anderson Live, September 24, 2012; also at http://www.drdansiegel.com/resources/video_clips/ then scroll down for 2012 videos

FN3 Najavits, Lisa M., PhD, Assoc. Prof of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School and Director Trauma Research, McLean Hospital, “Book Review, ‘Remembering Trauma’ by Richard McNally,” Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, Vol. 192, No. 4, April 2004 http://www.seekingsafety.org/7-11-03%20arts/4-04%20fin%20SCAND%20VERS-jnmd%20rev%20mcnally.pdf

FN4 http://www.mindful.ca/in-detail/the-sixtine-brain/

FN5 Porges, Stephen, PhD, 2013: “Body, Brain, Behavior: How Polyvagal Theory Expands Our Healing Paradigm,” NICABM Webinar, http://stephenporges.com/images/NICABM%202013.pdf

— On Trauma, 2013: “Beyond the Brain: How the Vagal System Holds the Secret to Treating Trauma,” http://stephenporges.com/images/nicabm2.pdf

— Academic background, 2001: “The polyvagal theory: phylogenetic substrates of a social nervous system,” International Journal of Psychophysiology 42 Ž, 2001, 123 146, Department of Psychiatry, Uni ersity of Illinois at Chicago, http://www.wisebrain.org/Polyvagal_Theory.pdf

Must-read interview: Siegel, Daniel J., MD, “Early childhood and the developing brain,” on “All in the Mind,” ABC Radio National, Radio Australia, June 24, 2006 at: www.abc.net.au/rn/allinthemind/stories/2006/1664985.htm

Books by Dan Siegel:

–“The Developing Mind: How Relationships and the Brain Interact to Shape Who We Are,” (Guilford, 1999). How attachment in infancy and childhood creates the brain and the mind.

–“Healing Trauma: Attachment, Mind, Body, and Brain,” Marion F Solomon, Daniel J Siegel, editors, New York, NY: W.W. Norton and Company; 2003. 357pg Reviewed by Hilary Le Page, MBBS at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2553232/

–“The Mindful Brain: Reflection and Attunement in the Cultivation of Well-Being,” (Norton, 2007)

–“The Mindful Therapist: A Clinician’s Guide to Mindsight and Neural Integration,” (Norton, 2010)

–“Mindsight: The New Science of Personal Transformation,” (Bantam, 2010)

–“Parenting from the Inside Out: How a Deeper Self-Understanding Can Help You Raise Children Who Thrive,” (Tarcher/Penguin, 2003) with Mary Hartzell

–“The Whole-Brain Child: 12 Revolutionary Strategies to Nurture Your Child’s Developing Mind,” (Random House, 2011) with Tina Payne Bryson, Ph.D

–“Brainstorm: Power and Purpose of the Teenage Brain,” (Tarcher, 2013)

![]()

Great post! I wish to subscribe to your newsletter.

Pingback: pre-verbal memories are accessible to EMDR traumatic interventions | in2uract

Pingback: thinking out of the box goes neonatal….. | seeking spirit

Thanks for this website, Kathy, and for spreading the word. I’ve followed the debate about memories and how they relate to childhood maltreatment for many years and have had a chance to read the viewpoints of van der Kolk, Jennifer Freyd, McNally’s group, Bruce Perry, etc. What becomes clear is that there is a powerful fear that keeps the average person from wanting to face and realize the power of those early years in our lives. But like you say “It’s gonna hurt!….” so the fear of “going there” is often understandable. Imagine a culture that actually encouraged that journey and supported you along the way instead of questioning your motives? Unfortunately, I still feel we are at the tip of the iceberg even on a research level in what manner and to what degree the brain and body are affected by early trauma/deprivation and what best would foster healing. But we have to start somewhere.

As for the New York Times Magazine article on PTSD and body-based recovery, it’s always my hope that authors of such pieces might be interviewed in their 70s and 80s to see if they have changed their tune on such a writing. So often the recognition of the impact of an early nurturing environment on one’s adulthood requires significant maturity, in accumulated years if not in emotional development.

Dear John,

I’ve been traveling (no computer) a week, so please forgive my delay.

My heart goes out to you if as seems, you’ve done the hard work of going down into early memory and feeling what hurts. Gosh it is terrifying and the pain feels life-threatening.

I wish I’d had more people like you to be with when I was in that journey. Or today.

Either way, your deeply perceptive comments are greatly appreciated.

Yes, I’m tired of being an “outlier” as I’ve been called, and I’d love to see as you describe it, “a culture that actually encouraged that journey and supported you along the way instead of questioning your motives” ! Bravo, John! Thank you so much, Kathy

Pingback: My theory: Why quality RAD treatment is hard to find

Dear Dr. Lien,

As I wrote you in April, I’m grateful for your work on how a traumatized infant’s brain learns so early to try to meet its own needs, that “mom” is terrifying. I’m that child and I know. I can feel it.

I’m grateful for your comments on my blogs, in your June 23 post “My theory: Why quality RAD treatment is hard to find” [http://instituteforattachment.org/theory-quality-rad-treatment-hard-find/ ]

And I’m grateful for your post! Indeed people are terrified to “accept that early abuse affects children’s brains” and “don’t want to accept child abuse and neglect in the first place—it’s too painful.”

Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) Study co-director Dr. Vincent Felitti, MD says so clearly: “Our findings…imply the basic causes of addiction lie within us and the way we treat each other, not in drug dealers or dangerous chemicals,” Dr. Felitti states… “Because cause and effect usually lie within a family, it is understandably more comforting to demonize a chemical than to look within,” he concludes. See: http://attachmentdisorderhealing.com/origins-addiction/

Sure, no one told you in grad school. No one tells in medical school, either, Felitti says: “In fact there was no basis for any opinion about the prevalence” of childhood trauma before the 1995-1998 ACE Study. “That’s because such information is almost completely protected by shame and secrecy, by families, and by individuals. Doctors also have been inhibited by our own ignorance and major gaps in our training, from asking into certain areas of patient history.”

When he first heard of ACE trauma from his patients, Felitti says, “I thought, ‘This can’t be true. People would know if that were true.

“Someone would have told me in medical school.’ / ”

Details and more evidence at: http://attachmentdisorderhealing.com/developmental-trauma/

Kathy