#10 in my ongoing book blogs from “Don’t Try This at Home”

After my Dad’s funeral, back I flew from Florida again to my consulting gig near Washington DC, and to Dan the rebound affair, who seemed supportive. I was so relieved to be away from the funeral pain, and being with Dan at his farm felt good.

Imagine my surprise when within five days of my father’s death, Dan sat down to the nice dinner I’d prepared for him one night and asked me to leave.

Imagine my surprise when within five days of my father’s death, Dan sat down to the nice dinner I’d prepared for him one night and asked me to leave.

“It’s just not happening for me,” he announced. “I want mah house back. I’m just not comfortable with you.” He had no feelings for me, he said. Whu Nhu? After almost two years and endless hours of intensity, I had been completely blindsided.

Later on that night (much later, after the inevitable rematch), I asked if he could let me know what I’d done wrong, so I could at least learn something from all this. All he could do was repeat “I was comfortable with Maureen (his ex). But you get so excited when you talk that you wave your hands and it distracts me to where I can’t hear what you’re saying. I’m just not comfortable with you.”

“I’m just not comfortable with you.” At the time it seemed merely unjust, but make a mental note of that turn of phrase. It will prove to be another clue to the big picture puzzle.

I left Dan’s farm and rented a room in an elderly widow’s home near the airport to work out my consulting contract for another three weeks, before I could escape back to California.

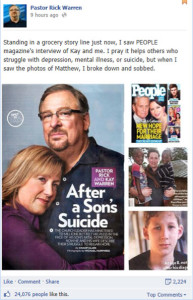

My Dad was dead — and still I couldn’t cry for him. But now I was crying buckets on the hour for Dan, a stranger I’d known only briefly over just short of two years.

Over the July 4, 2008 weekend I dutifully googled “Grief” on the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) website (since taken over by SAMHSA). I found this on page two, and in all these years, it’s by far the best way to confront grief I’ve ever seen, packed full of heavy truth in each short sentence:

“How will I know when I’m done grieving? Every person who experiences a death or other loss must complete a four step grieving process:

1. Accept the loss

2. Work through and feel the physical and emotional pain of grief

3. Adjust to living in a world without the person or item lost

4. Move on with life.

“The grieving process is over only when the person completes these four steps,” it concluded bluntly. This short but dense RX has since been inexplicably removed from the NIMH website, but I’ve kept a folded shard of the printout all these years. And it proved to be deadly accurate.

I posted “Accept the Loss” in Calibri 16 point font on my computer, my bathroom mirror, and taped it on my wallet (still there to this day), but I couldn’t begin to understand what it meant. I was dead sure that the shattering loss I was feeling was heartbreak over Dan.

I felt guilty but little more for my Dad.

Right on cue as my personal life went down the tubes, it sure did look as if I were in good company and the whole American economy were simultaneously going down in a hand basket.

I was working 14 hour days on a punishing schedule for the Transportation Security Agency (TSA) info-tech proposal. I could remember when a Defense Department proposal was just that: a large technical document written for a major defense supplier, explaining why our satellite system or computer system was better than the competitors’.

Here, however, at times I was sure I was in the Twilight Zone, there was such disorganization bordering on panic. This was a $2 billion project, to be built at hundreds of airports, ports and border crossings around the nation, and every large company in the U.S. was bidding. The company which retained me had thrown their entire budget for a year on this one proposal, bringing in consultants by the dozens — without setting up a reasoned structure.

It was mass chaos. We had computer gurus in turbans from Bombay, and Brits from London who would joke they were here to take back the colonies (to which I retorted “What’s left? There’s no industrial base…”). We had cost cutters from Lower Manhattan who didn’t care whether the equipment we were proposing to sell to Uncle Sam worked or not, if they could just structure the cheapest bid.

It was mass chaos. We had computer gurus in turbans from Bombay, and Brits from London who would joke they were here to take back the colonies (to which I retorted “What’s left? There’s no industrial base…”). We had cost cutters from Lower Manhattan who didn’t care whether the equipment we were proposing to sell to Uncle Sam worked or not, if they could just structure the cheapest bid.

We hardly had time to leave our desks to eat and by the last two weeks they were trucking in catered breakfast, lunch and dinner. Anonymous signs began to appear on doors spoofing the insanity. Yes, I saved one and scanned it today (above). Click on it, it’s a riot.

Through the din, every morning at 8 am there was a voice on the speaker phones throughout the building, the voice of the lady Proposal Manager, literally shouting orders to the massed troops. One day I had to tear myself from my workstation long enough to go down to the basement super-bunker to interview some of the top brass leading the project. There in what looked like a 5-foot wide loud yellow shirt was a woman who resembled nothing so much as Jabba the Hut, scratching her arms, chain smoking, and shrieking into the speaker phones. “Well, she’s won $10 billion worth of proposals, so whatever Lola wants,” one fellow muttered.

I really wasn’t very sure I wanted to be in this line of work anymore. But what choice did I have – starve to death alone?

It was as if that Twilight Zone had engulfed my public and my private life in one nasty slurp.

I was leading a double existence, interviewing top executives by day, then crying into the cell phone to my friends in California on my short breaks, standing outside in the muggy Virginia heat. It had all been a series of psychological champagne drunks I was on, I told them ruefully, to cover up my divorce, the fact that I had lost my 27-year marriage, my overseas projects, my music, and my whole life.

I couldn’t “Accept the loss” of my entire life, or my divorce; I couldn’t accept anything. I just ran. First I ran to Dan, then to California dancing, singing Country, sailing, and dating, then back to Dan, I told them. Now I’ve lost the Dan umbilical cord to the East Coast and I belong nowhere.

So what do you do when the champagne factory shuts down? After everyone left the office at 11 pm I stayed on, churning out Dan doggerel well into the early morning.

I didn’t feel any anger at all while I was crying so hard during that summer of 2008; I don’t recall feeling anything like anger for another four years. I just felt unloved, deadly lonely and miserable.

But I still had an empty string bean can with a half dozen jagged wounds, from the day Dan posted it as a target at the far end of a back woods field as part of his efforts to teach me to shoot pistols. Something inside me resonated oddly, to think that I had actually pumped this piece of metal full of lead.

But I still had an empty string bean can with a half dozen jagged wounds, from the day Dan posted it as a target at the far end of a back woods field as part of his efforts to teach me to shoot pistols. Something inside me resonated oddly, to think that I had actually pumped this piece of metal full of lead.

I may not have been aware of any anger, but my reaction to that piece of junk and the poems told another story which didn’t come out until much later.

Tin Can Shot Full of Holes

(Apologies to Bob Seeger)

July 12, 2008

It’s sitting on the wall ledge above my closet door,

It sits and stares right at me; I know what it’s staring for:

To think a serious woman like me would be concerned,

For such a pile of tin and rust, and might even get burned.

The more I think about it, the less I can control

A visceral reaction to that tin can shot full of holes.

I met a man in Mexico, he had an eagle eye,

He warned me not to go too far, he warned me not to die;

He warned me there was nothing alive behind his smile;

He smiled so warm right through me it almost seemed worthwhile.

I thought his smile might save him, as bright as burning coal,

But nothing could bring comfort to a tin can shot full of holes.

We went up on the mountain with little more to say,

I did my level best to focus on things far away,

We used tin cans as targets for pistol practice shots,

But never could be certain to hit any given spot.

With Dorothy, I’ve traveled over Oz from pole to pole,

But all I’ve come away with is a tin can shot full of holes.

I hate it when these poems just overflow my mind;

I’d rather more be sleeping and my work is far behind.

I see him in the shadows, I see him in the sun,

I see him on the grasslands, I see him on the run,

He’ll have to run forever, for he’s running from his soul;

My heart goes out in pity to the tin man shot full of holes.

Hit Bottom Yet?

By the time I flew back to California on July 18, 2008, tail between legs, I was in bad shape. But think you’re hurting now, girl? Ha. It was just the beginning.

Now the Great 2008 Financial Crisis meltdown was in full swing, banks were crashing left and right across America, and my aerospace engineering and IT consulting market on the West Coast suddenly folded up like a Japanese duck pop.

“Japanese duck pop” is a semi-controversial term I’ve been accused of making up, but which I’m sure I learned from a Korean War Vet in some global timezone at some point in the 1990s. Imagine a flock of ducks flying along, and one of them while zipping straight ahead at a good clip, sticks his head directly up his rear… until pop! He simply disappears, in Incheon Landing slang.

An opera-going friend invited me to an elite dinner party in Newport Beach, where of course I did not use this sort of language. One thing I know how to do is put up a glamorous front at an upscale dinner party. The woman seated to my right asked my line of work. “You’re a writer? Fabulous,” she said. “I run an investment fund; my clients invest a minimum of $5 million with me. I want to publish a book on my investing method and I’d like you to be my ghost author. Come to my office on Monday.”

Soon I was in her impressive Newport Beach office, complete with fountains in the palm-swept courtyard, taking down her book in dictation twice a week, as she rattled it off the top of her head. Soon we were talking international finance, and she was talking about taking me on to train me to help handle some of her millionaire investment clients. Magic! A new California Dream.

Until one day I sat down in her office – and the investment bank on Wall Street where she kept all her clients’ funds had just gone down in flames, bringing the markets with it. Her cell phones were ringing, the computers were going haywire, her irate clients were pulling up in limos, and her husband and son were running in and out of the room with slips of paper and messages.

It was like trying to write a book on nuclear war, in the middle of a nuclear war. There went another California Dream. The Great 2008 Financial Crisis made an end to that book project, along with major investment banks.

It was like trying to write a book on nuclear war, in the middle of a nuclear war. There went another California Dream. The Great 2008 Financial Crisis made an end to that book project, along with major investment banks.

It was also the end of my California defense career, because the Federal proposal consulting market in California suddenly died, never to be born again as of today. All the technical writing jobs for aerospace engineering near Los Angeles International Airport which I had been eying suddenly were shipped back to the Washington DC Beltway from whence I’d just barely escaped with my life.

I’d put some cash away from all those contracts, but that career was gone, unless I wanted to move back to Washington, world capital of defense consulting, home of the rain, sleet, and the long shadow of Dan Heller. I did not; I physically could not. I was sick to my gut at the thought of travel to the East Coast.

So I was stuck in my one-room in California, which was actually little more than a shack in a young couples’ back yard, with the clothes on my back, $30K in my ex’s debt still on my credit cards, my hard-earned savings, and a stellar resume – curled up in a heap on my bed like a spider checking out for good.

Did I mention that I’d tried dating in California? I did meet several fellows. One was Harvey the Vietnam vet, a sweet man who bore a striking resemblance to Tarzan (he was ripped). Harvey had survived some horrible experiences in combat, though. And now I was beginning to feel like I knew just what he had been through.

Summer 2008, I thought, surely was the the end of my world. Surely it could get no worse than this. One of my journal entries at the height of the 2008 Presidential campaign gave some pretty amazing evidence on my state of mind:

The Helicopter

(Apologies to Senator McCain)

August 2, 2008

My friend Harvey fought in Vietnam as a combat photographer,

At 6’3″ he weighed over 220 pounds.

On one evacuation the GIs pushed him off the helicopter:

“Pansy photographer! We can’t take off with your weight!”

Harvey was captured by the Vietcong. Eventually he escaped.

Sometimes I have that helicopter feeling:

That my parents threw me out of my house,

That my husband threw me out of my life,

That the economy threw me off of the bus.

I forsook my family and gave up everything for you,

But you threw me out of my life,

You threw me into the world completely unequipped,

To know that I was prey.

You threw me, without ever having been loved,

Into Superman’s arms,

He took me for a flight, and I thought “Oh, maybe this is love?”

But soon he was done — and he threw me off the helicopter

—————————–All

———————————————Over

—————————————————————–Again.

Bang! You’re dead. All over again.

I’m MIA — and no one even knows I’m missing,

Or will know whether I die or whether I live…

I’m MIA — and I can’t even run for President;

I don’t even have the dignity of a dog tag.

———————————

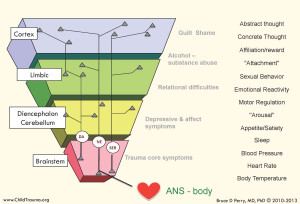

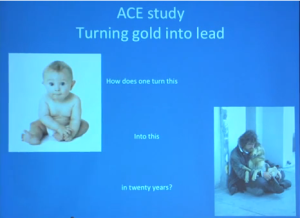

This is from Chapter 2 Part II of Kathy’s forthcoming book DON’T TRY THIS AT HOME: The Silent Epidemic of Attachment Disorder – How I accidentally regressed myself back to infancy and healed it all. Watch for the continuing series of excerpts from the rest of her book every Friday, in which she explores her journey of recovery and shares the people and tools that have helped her along the way.

![]()