CLICK to BUY “Don’t Try This Alone”

CLICK to BUY “Don’t Try This Alone”

Neuroscientist Dr. Stephen Porges appeared in my last few blogs; let’s explore his 1994 discovery of the Polyvagal Theory. Dr. Porges runs brain-body research at top psychiatry departments (University of Chicago and University of North Carolina Chapel Hill).

And he always says he wasn’t looking for a polyvagal theory. He was just researching ways to measure the vagus nerve, the 10th cranial nerve running between the brain stem and most of the body.

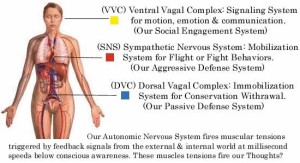

Until 1994, textbooks said there are two parts to the autonomous nervous system (ANS). First, the sympathetic system mobilizes us for fight and flight, but is harmful if it stays on too long, making us tense, anxious and prone to disease. Second, the parasympathetic inhibits mobilization, so it was believed to be calming and healthy. Textbooks taught that “the net result was a balance between a pair of two antagonistic systems,” Porges says. The vagus nerve makes up a chunk of the parasympathetic; “it functions like a brake on the heart’s pacemaker.” [FN]

This two-part model broke down “as I was conducting research with human newborns to measure heart rate, assuming vagal activity was protective,” Porges says. “If newborns had good clinical outcomes, they had a lot of vagal heart rate going up and down with breathing. Babies with flat heart rates were at risk. So I wrote a paper in the journal Pediatrics to educate neonatologists.

“Following publication, I received a letter from a neonatologist who noted that… the vagus could kill you, and that perhaps too much of a good thing was bad. His comments startled and motivated me to challenge our understanding of the nervous system.

“I immediately understood what the neonatologist meant. From his perspective, the vagus can kill, since it is capable of life threatening bradycardia and apnea — massive slowing of heart rate and cessation of breathing. For many pre-term infants, bradycardia and apnea are life threatening. I now framed the ‘vagal paradox.’ How could the vagus be both protective and lethal? For months I carried the neonatologist’s letter in my briefcase.”

Poly Faces of Vagus

Porges went back to the evolution of anatomy, and saw that in fact there are two different vagus circuits — a total of three ANS circuits, not just a pair. The two circuits “come from two different areas of the brain stem, and they evolved sequentially,” one far earlier.

“This motivated me to develop the polyvagal theory, which uncovered the anatomy and function of two vagal systems, one potentially lethal, and the other protective,” he says.

“Immobilization, bradycardia, and apnea are components of a very old, reptilian defense system, ” Porges says. “If you look at reptiles, you don’t see much behavior — because immobilization is the primary defense system for reptiles… it’s an ancient vagus nerve.” This pre-historic nerve has no myelin, a nerve coating of protective protein and fat.

Porges found mammals have this unmyelinated vagus, on the dorsal (top) side of the nerve, which immobilizes us, too — “and that immobilization reaction, adaptive for reptiles, is potentially lethal for mammals.”

Porges also saw that among the “firsts” which began with mammals, a new vagus with myelin develops on the ventral underside of the nerve. “So mammals have two vagal circuits,” he found. ” The myelinated circuits provide more rapid and tightly organized responses. The new mammalian vagus is linked to brain stem areas that regulates the muscles of the face and head. Every intuitive clinician knows that if they look at people’s faces and listen to voices, controlled by muscles of the face and head, they know the physiological state of their client.”

Neuroception: It’s Just Not Cognitive

Porges adds that our more primitive neural circuits operate by “neuroception” — totally involuntarily. “Neuroception is not perception,” he says. “Neuroception does not require an awareness of things going on. It is detection without awareness. It is a neural circuit that evaluates risk in the environment… When confronted in certain situations, some people experience autonomic responses such as an increase in heart rate and sweating hands. These responses are involuntary. It is not like they want to do this.”

The polyvagal theory emphasizes that our nervous system has more than one defense strategy – and whether we use mobilized flight/flight or immobilization shutdown, is not a voluntary decision. Outside the realm of our conscious awareness, our nervous system is continuously evaluating risk in the environment, making judgments, and prioritizing behaviors that are not cognitive.

Next, he says, “humans and other mammals, as fight/flight machines, only work if they can move and do things. But if we are confined, if we are placed into isolation, or if we are strapped down, our nervous system reads those cues and functionally wants to immobilize. I can give you two interesting examples: one is a news clip I saw on CNN and the second from my own personal experience.

“I saw a CNN news broadcast with a video clip of a plane whose wings were tipping up and down as the plane was tossed by the wind. The plane did land safely and the reporter went to interview the people. He asked one of the passengers how it felt to be in a plane that looked like it would crash. Her response left the reporter speechless. She said, “Feel? I passed out.” For this woman, the cues of a life threat triggered the ancient vagal circuit. We don’t have control over this circuit.

“Many people who report abuse especially sexual abuse, experience being held down or physically abused. These abused clients often describe a psychological experience of not being there. They dissociate or pass out. The abusive event triggered an adaptive response, to enable them not to experience the traumatic event.”

Porges’ second example, noted in my Aug. 22 blog, was his own attempt to have an MRI – in which his body flat out overruled his powerful thinking brain. “I wanted the MRI. But something happened to my body when I entered the MRI that triggered my nervous system into…wanting me to mobilize to get out of there.” So the nurses let him out.

Porges was asked by one interviewer, “What would have happened if you called to be let out — but no one came?”

“Now we’re talking!,” said Dr. P. “So now I am stuck in there, I can’t get out; I am in this confined area. That would be totally like being physically abused, being held down, going through all these same things.” Like the plane passenger who defaulted back in evolution to her most primitive system, he might have dissociated or passed out.

“The problem, of course, is how do you get people back out of that?” Porges asks. ” If a life threat puts a human into this state, it may be very difficult to reorganize to become ‘normal’ again.”

Friday Sept. 26: Videos and audios on Polyvagal Theory

Friday Oct. 3: Dr. Porges on how to “get people back out of” the reptilian freeze of trauma.

——————

Kathy’s news blogs expand on her book “DON’T TRY THIS AT HOME: The Silent Epidemic of Attachment Disorder—How I accidentally regressed myself back to infancy and healed it all.” Watch for the continuing series each Friday, as she explores her journey of recovery by learning the hard way about Attachment Disorder in adults, adult Attachment Theory, and the Adult Attachment Interview.

Footnotes

FN Porges, Stephen, PhD, “The Polyvagal Theory for Treating Trauma,” 2011, http://stephenporges.com/images/stephen%20porges%20interview%20nicabm.pdf

—“Body, Brain, Behavior: How Polyvagal Theory Expands Our Healing Paradigm,” 2013, http://stephenporges.com/images/NICABM%202013.pdf

—“Beyond the Brain: Vagal System Holds the Secret to Treating Trauma,” 2013, http://stephenporges.com/images/nicabm2.pdf

—”Polyvagal theory: phylogenetic substrates of a social nervous system,” International Journal of Psycho-physiology 42, 2001, Dept. of Psychiatry, Univ. Illinois Chicago, www.wisebrain.org/Polyvagal_Theory.pdf

![]()

Pingback: Nurture Your Child's Survival Instincts

“But if we are confined, if we are placed into isolation, or if we are strapped down, our nervous system reads those cues and functionally wants to immobilize. ” This explains why some of the toughest fighters most gung ho Marines faint on the spot when they get a vaccine injection.

They can’t do “fight or flight” to either punch out the nurse or run away from being jabbed with the needle, which would be a very basic animal instinct reaction to being “attacked” by the needle jabbing, so they pass out -the immobilizing vagus nerve reaction.

This is fascinating. Over 40 years ago as a young doctor working in an Emergency Room in inner city Dublin, we were so overcrowded that I risked taking blood samples from patients standing up . We had run out if chairs and people were lined up seeking care. I first chose a big burly young man , who I thought looked tough enough to survive the prick of a needle. He promptly collapsed on top of me as he fainted. The nurses scolded me and told me to pick little old ladies. These tiny creatures never fainted. My patient survived and so did I. The old ladies did not faint. I am one myself now and able to cope with limited poking.

Very2funy

Pingback: Down to Earth, Vagabond Nerve | PTSD FORUM

Porges’ affiliations, per his website: “Dr Porges is a Distinguished Scientist at the Kinsey Institute at Indiana University and Research Professor, Department of Psychiatry, University of North Carolina. He is Emeritus Professor, of Psychiatry, University of Illinois Chicago and of Human Development, University of Maryland.”

Pingback: DRS. Stepehen Porges and Nadine Jacqueline Burke Harris on TRAUMA AND RESILIENCE | People's Advocacy Council

Pingback: Dr. Nadine Burke Harris TED Talk National Public Radio | People's Advocacy Council

Glad to see you with Dr. Porges’ book! Have you seen Dr. Bessel van der Kolk’s 25th annual Boston Trauma Conference lecture DVDs? Marty Teicher is superb from the 22nd conference! I keep listening to the lectures over and over!!!